The Johannine Comma by Colin Tyler

Posted on

The Three Heavenly Witnesses. (The Authenticity of 1 John 5:7)

"For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one."

This verse is found in the KJV Bible but is missing from a great many, perhaps most, later English bibles. It is a very clear declaration of the reality of the Holy Trinity. Those who maintain, like myself, that the King James Bible is the perfect word of God in English, see its removal from modern bibles as part of the modern attack upon sound doctrine. In this case, the Trinity.

Two wonderful books written in defence of the authenticity of this verse have been a great encouragement to me. They are, A History of the Debate over 1 John 5:7 by Michael Maynard, published in 1995, and Letters to Edward Gibbon, Esq. by George Travis, published in 1785.

Maynard's book is exactly what he says it is. He traces from the first century to the present day the pro and con debate over the verse and the parties concerned. This is a very useful resource, though I must confess that I have only used it for occasional reference rather than a cover to cover reading.

Travis's book I found hard to put down and was so pleased with it that I read all 376 pages of it twice through, excepting the appendices, which are almost all in Latin as taken from earlier authors such as Jerome (AD 347-420).

My plan here is to try and give in simple terms some of the meat of Travis's work for Christians who might be troubled by the doubts being cast upon the verse. In dealings with so-called Jehovah's Witnesses, who do not believe in the Trinity, this can be a powerful verse but we must be ready to defend it.

George Travis, was Archdeacon of Chester from 1786 until his death in 1797. His defence of 1 John 5:7, often referred to as the Johannine Comma, comprises five letters addressed to Edward Gibbon, author of the famous work, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Travis takes Gibbon to task for his comments on 1 John 5:7, hereafter, 'the comma'.

Internal and External Evidence.

Arguments for or against biblical texts are often made from what is called Internal Evidence or External Evidence. Internal evidence has to do with whether the disputed words agree with the biblical context in which they are found or not found, or with biblical truth as a whole. That is to say, does the passage in the Bible make more sense with or without the disputed text? External evidence has to do with how the manuscripts (MSS) read and how they compare with one another.

External evidence is by far the most complex form of evidence, and on this particular verse, opens up a massive, though very interesting, field of investigation. This form of evidence is very much the realm of scholars and perhaps would not appeal to every Christian. It seems to me, however, that no matter how deep down the rabbit-hole you go, there are still those both for or against the text. I will mention some of this evidence in the second part of this article.

I shall subdivide what follows under three headings.

1. Internal Evidence.

2. External Evidence.

3. Scholasticism.

Internal Evidence for the Authenticity of 1 John 5:7.

To keep this study as simple as possible, I will argue first from the standpoint of internal evidence. Internal evidence may be taken from the English or the Greek Text. I will focus mainly on the English but there are some important points also to be made from the Greek texts.

In studying John's first epistle recently, I was struck by his insistence both upon the deity and the humanity of the Lord Jesus Christ. For example, concerning Christ's deity, John writes,

"Whosoever shall confess that Jesus is the Son of God, God dwelleth in him, and he in God." ch.4:15

And concerning the Saviour's humanity,

"That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, which we have looked upon, and our hands have handled, of the Word of life;.." ch.1:1

These two truths regarding the Saviour's deity and humanity form a thread running right through this first epistle of John. In the first chapter of John's gospel we meet immediately with the same two truths.

"In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God." ch.1.1

and,

"And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us,.." ch.1:14

Why does John say so much about this in his epistle? Because he lived very close to the end of the first century and he had seen the development of heresies concerning the person of Christ.

George Travis, in his letters to Edward Gibbon, describes these heresies. By the time John writes his first epistle, there were at least three major heretical groups promoting error concerning the Lord Jesus. Here's what Travis has to say concerning two of them,

"Before this epistle was written, the two, opposite, heresies of the Cerinthians, and the Docetists,1 had arisen, to the great disturbance of the Christian Church. The Docetists denied the incarnation of Christ; refusing to admit that he was ever clothed with human flesh, or ever took our nature upon him. The Cerinthians, on the contrary, denied his divinity; affirming the Jesus Christ had no other than the human. Against such errors as these it was highly needful to protest, and to contend for the faith once delivered to the saints: and St. John alone, probably, then remained, of the sacred College of the Apostles, to undertake the work with the authority of an inspired writer.

"In a few of the first verses of his Gospel he asserts the God-head of the Word, the Almighty, and Eternal Word, in confutation of the errors of Cerinthus. 'In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. The same was, in the beginning, with God. All things were made by him; and in him was life."2 And in a succeeding verse, he stops to affirm the incarnation of Christ, with a plainness, and precision, equally fatal to the opposite error of the Docetists. 'And the Word was made flesh and dwelt among us.' He condemns the Docetists also in the exordium of this epistle. 'That which was from the beginning, which we have heard, which we have seen with our eyes, and our hands have handled, of the Word of life: declare we unto you.' He confounds the Cerinthians in the close of it. 'And we know that the Son of God is come, and hath given us an understanding that we may know him that is true; and we are in him that is true, even in his Son Jesus Christ: This is the true God and eternal life.'

"These separate condemnations are found united together, and are urged in conjunction, in that passage of this epistle, which is the object of this present disquisition, and in a few words antecedent, and subsequent, to it. The text stands, literally, thus:

'This is the victory that overcometh the world; even our faith. Who is he that overcometh the world, but he that believeth that Jesus is the Son of God? This is he that came by water and blood, even Jesus Christ; not by water only, but by water and blood. And it is the Spirit that beareth witness, because the Spirit is truth. For there are three that bear record in heaven, the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one. And there are three that bear witness in earth, the Spirit, and the water, and the blood: and these three agree in one...

"And these words may, in the sense just stated, be thus paraphrased.

"It is this conviction, which giveth us that victory which overcometh the world, which rises superior to its terrors, as well as to its temptations, even our faith that Jesus is the Son of, a partaker of the same nature with, God. But this Jesus is not a partaker of the divine nature, only; for, when he came on earth, he took our human nature also upon him, as appeared by the Water, and Blood, which flowed from his side, when pierced by the spear upon the cross. These two truths, directly opposite to both your errors, ye Cerinthians, and ye Docetists, are established by the most powerful proofs. For there are three in heaven, that bear record to the divine nature of Christ; namely, the Father, who declared by his own voice from heaven, This is my beloved Son, in whom I am well pleased; the Word, who continually affirmed of himself that he was the predicted Messiah, that he had existed before Abraham, that he was the true Christ, the Son of God; and the Holy Ghost, who descended, in bodily presence, like a dove, upon his head, at his baptism, and sat in cloven tongues, like as of fire, upon the heads of his apostles after his resurrection. And these three are one in nature, or, at least, in unity of testimony, proving against you, ye Cerinthians, the divinity of Jesus Christ. And there are (moreover) three which bear witness on earth, against you, ye Docetists; and these three agree in one, as to the reality of Christ's taking our human nature upon him: namely, the Spirit, Soul, or Life, which he breathed forth upon the cross, when he gave up the Ghost; and the water, and the blood, which flowed from his side...when they looked on him whom they pierced. These, ye Cerinthians, these, ye Docetists, are the testimonies which overthrow both your errors: proving Jesus Christ to have a divine, as well as a human, nature; to be God as well as man."3

Thus, the subject of John's first epistle, perfectly correlates with the subject of the comma. This is strong internal evidence in favour of the verse.

There is also a very interesting internal consideration in favour of the verse when its place is retained in Greek texts. Greek nouns have gender. That is, some nouns are masculine, some are feminine and some are neuter. If verse seven is removed from the Greek texts, the resulting reading, as found in modern Greek texts, is made to violate a rule of Greek grammar. Dr. J. A. Moorman explains,

"If the passage is removed from the Greek text, the two loose ends will not join up grammatically. A problem arises which has to do with the use of the participle which is a kind of verbal adjective. Being an adjective it modifies nouns and must agree with them in gender.

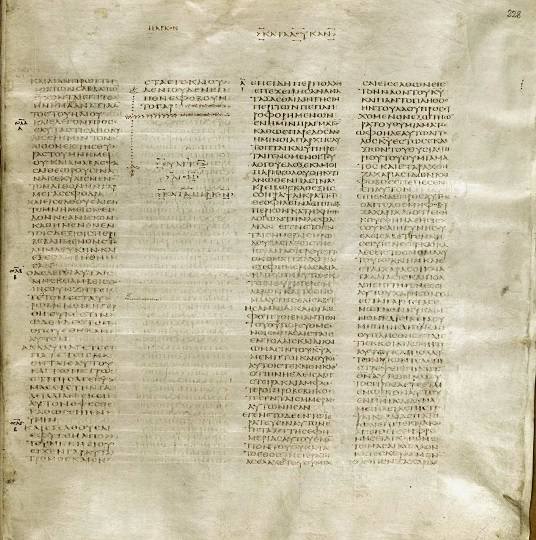

"With the full passage set out, it becomes apparent how this rule of grammar is violated when the words are omitted. The disputed words are enclosed in square brackets.

"vs. 6 And it is the Spirit (neuter) that beareth witness (neut.) because the Spirit (neut.) is truth.

"vs. 7 For there are three (masculine) that bear record (masc.) [in heaven,

the Father (masc.), the Word (masc.), and the Holy Ghost (neut.):

and these three (masc.) are one (masc.).

"vs. 8 And there are three (masc.) that bear witness (masc.) in earth]

the Spirit (neut.), and the water (neut.), and the blood (neut.): and

these three (masc.) agree in one.

"Note that the underlined words "that bear witness" are participles. If a textual critic wants to remove this passage he should be able to answer the following:

"1. Why after using a neuter participle in line one is a masculine participle suddenly used in line three?

"2. How can the masculine numeral, article (in the Greek), and participle (i.e. three masculine adjectives) of line three be allowed to directly modify the three neuter nouns of lie seven?

"3. What phenomena in Greek syntax would cause the neuter nouns of line seven to be treated as masculine by the "these three" in line eight?

"There is not a good answer! And perhaps this is the reason why such leading Greek scholars as Metzger, Vincent, Alford, Vine, Wuest, Bruce, Plummer, do not make the barest mention of the problem when dealing with the passage. The International Critical Commentary devotes twelve pages to the passage but is as quiet as the proverbial turkey farm on Christmas afternoon regarding the mismatched genders."4

That looks like a slam dunk to me!

Another grammatical problem is also raised by Thomas F. Middleton, whom I will quote to close this discussion of internal evidence.

Dean John Burgon said that the authority on the Greek article was Thomas Middleton. Thomas Fanshaw Middleton was Bishop of Calcutta and wrote, The Doctrine of the Greek Article, Applied to the Criticism and Illustration of the New Testament in 1833. Personally, this appears to be one of the most learned works in my possession and makes me feel that I have the brains of a crustacean.

In this remarkable book, Dr. Middleton has a discussion of the Greek article in reference to 1 John 5:7 & 8. Dr. Middleton favourably cites some of the most hostile critics of the text such as Richard Porson and J. J. Griesbach. He begins by saying,

"Everyone knows of how much controversy this passage has been the subject and that the words which I have enclosed in brackets [the comma.] are now pretty generally abandoned as spurious."5

After recommending certain works for study regarding the comma, he continues,

"The probable result will be, that he will close the examination with a firm belief that the passage is spurious;.."6

There then follows a very learned consideration of what Dr. Middleton considers to be a grammatical problem with the end of verse 8 if verse 7 is rejected. This is not the same grammatical difficulty covered by Dr. Moorman above, but another. The last four Greek words of verse 8 include the neuter definite article 'το'. Middleton writes,

"...if the seventh verse had not been spurious, nothing could have been plainer than that the ΤΟ εν7 of verse 8, referred to εν of verse 7: as the case now stands, I do not perceive the force or meaning of the Article."8

After a long and learned consideration of why this anomaly should occur when verse 7 is omitted, Middleton concludes,

"On the whole I am led to suspect, that though so much labour and critical acuteness has been bestowed on these celebrated verses, more is yet to be done, before the mystery in which they are involved can be wholly developed."9

To summarise what Dr. Middleton has said, even though I have the brains of a crustacean and could not follow all his reasoning, some things are clear, even to me. At the start of his discourse on the subject he says that anyone studying the matter, "will close the examination with a firm belief that the passage is spurious." But he does not affirm that he has come to that conclusion himself. At the start of his discourse he states, "I do not perceive the force or meaning of the Article," At the end he confesses that the Greek construction, with the Greek article at the end of verse 8, remains to him a mystery if verse 7 is omitted.

So here is a major Greek scholar in 1833 (whose work on the Greek article is recommended by the redoubtable John William Burgon), saying that he could find no convincing reason (after combing the New Testament, the Septuagint and the Greek classics) for the Greek reading of verse 8 without the presence of verse 7.

On the basis of internal evidence then, of the English and Greek texts, the modern critics case looks pretty shabby.

External Evidence for the Authenticity of 1 John 5:7.

To repeat what was stated above, external evidence has to do with how the MSS read and how they compare with one another.

Michael Maynard's book, A History of the Debate over 1 John 5:7-8, mentioned above gives names and dates and titles of works of those who have debated this issue from the 1st.

century until 1995. I think it quite plausible that the ink used in the manuscripts alone would probably be enough to fill a large swimming pool.

Naturally, over such a massive field of enquiry and discussion, I must be selective. I will be leaning heavily on this part of the article upon George Travis's work, Letters to Edward Gibbon Esq.

Travis argues strenuously and perspicaciously in favour of the inclusion of verse 7 as authentic scripture from the hand of the apostle John. Regarding external evidence he mentions many Greek manuscripts which are no longer in existence.

The critics ace card these days, which they play all the time, is the dearth at the present time of Greek manuscripts which contain the verse. Out of around 5230 Greek MSS, which in many cases are only portions or even a verse or two, only 8 or 9 contain the verse. This is their constant song. But the question should be asked, "Was it always so? Was there never a time when there were more Greek MSS with the verse in-situ?"

Travis begins by speaking of the Greek MSS copies that contained the verse in the early sixteenth century and describes the references to them by many authors and councils up to the close of the first century. He also refers to the early sixteenth century printed editions with some interesting claims about Greek MSS which were available to the editors.

With the invention of printing in the fifteenth century, handwritten copies, or manuscripts began to be replaced by printed Bibles and New Testaments. The major editions printed in the sixteenth century are,

Erasmus - 1516, 1519, 1522, 1527, 1535.

Robert Stephens (Estienne) - 1546, 1549, 1550, 1551.

Theodore Beza - 1556, 1565, 1582, 1589, 1598.

The first printed Greek New Testament was called the Complutensian Polyglot, which was printed in 1514 but not published until 1522. The first printed New Testament to be published was produced by the Dutch scholar Erasmus in 1516. Travis says that the Complutensian Polyglot was the product of 42 Spanish scholars working with GREEK manuscripts which they had from the Vatican library. A copy of the Complutensian Polyglot can be seen in the Gutenburg Museum in Mainz, Germany. It is a stunning document to look at and was evidently backed by a considerable sum of money under the oversight of Cardinal Ximenes, a Spanish Catholic. Strangely, for a Romanist publication, the text is very close to Erasmus and Stephens. It includes the comma.

So here is the first contradiction to the modern denial of Greek MSS testimony. The Complutensian used Greek MSS from the Vatican and they included the verse. It follows that it must have at least preponderated in those MSS. Travis writes concerning the Complutensian,

"It was the result of the joint labours of many learned men, who were selected, by the Cardinal, for that purpose, and furnished with all the Greek MSS, and other aids, which his great political, as well as personal, influence could procure. In this work the 'Complutensian editors' have inserted the text of 1 John 5:7:..."10

With this statement Daryl R. Coates concurs, writing in1994.

"Cardinal Ximenes said this about the manuscripts he used for the Complutensian Polyglot New Testament (which also contained 1 John 5:7): 'For Greek copies indeed we are indebted to [Pope Leo X], who sent us most kindly from the Apostolic Library very ancient codices, both of the Old and New Testament, which have aided us in this undertaking.' (cited by Metzger, Text of the New Testament, p. 97; emphasis added.)11

Evidently, in the beginning of the sixteenth century there were sufficient Greek manuscripts to convince the Spanish editors of the authenticity of the comma. Possible causes of the diminishing numbers we shall consider below.

Erasmus' behaviour is a little strange and is much more the focus of modern critics. His first two editions of the printed Greek New Testament were published in 1516 and 1519. Neither of these contained the comma. His three subsequent editions of 1522, 1527 and 1535 all contained it although modern critics, according to Maynard, seem unsure.12 The strange conduct of Erasmus is highlighted by the materials Travis claims were used by Stephens just 34 years later in his 1550 edition. Concerning Robert Stephens editions, I will quote Travis at length.

"In AD 1546 , Robert Stephens published his valuable edition of the Greek Testament. That this work might be as perfect as possible, great industry was used to collect such Greek MSS, as had escaped the enquiries of the editors of Complutum. And those endeavours were attended with such success, that Robert Stephens in the prosecution of that work, 'collated his Greek text with sixteen very ancient, written, copies.' This edition of AD 1546, and a subsequent one in AD 1549, not being printed in a volume large enough to admit of marginal remarks, and notations of different readings, contained only the plain Greek text of the New Testament. And in both these editions stands this testimony of the three (heavenly) witnesses. In AD 1550, Robert Stephens gave a third edition to the world, on a larger scale: in which he distinguished the different Greek MSS, which he had collated, by Greek letters (β, γ, etc.) and the various readings by an obelus and semi-parenthesis, or crotchet; which, wherever inserted, were meant to denote, that, from the word, before which the obelus was placed, to the station where the semi-parenthesis was found, in the Greek text, the whole of that verse, or verses, word, or words, was wanting in the particular MSS cited in the margin. In this third edition, Robert Stephens has thus marked, in a great variety of instances, sometimes a single word alone, and sometimes several words following each other. As he found in several of (for it seems to have existed in them all) his own Greek MSS, and in the Complutensian Bible, this seventh verse entire; so in some others he remarked the particular words (εν τω ουρανω) 'in heaven,' to be wanting. At the head of these three words, therefore, Robert Stephens placed an obelus, in his edition of AD 1550, and a semi-parenthesis at the end of them: thereby denoting, to the reader, that those three words were wanting in the particular MSS, referred to in the margin.13

To illustrate Stephens' markings of the omission of the words 'in heaven', in his printed edition, the words would be marked thus,

"For there are three that bear record † in heaven ) the Father, the Word, and the Holy Ghost: and these three are one."

In the margin of his printed edition at the end of the line where the obelus and semi-parenthesis appear, Stephens would designate the MS or MSS which omitted the words.

Those who oppose the inclusion of the comma have argued that Stephens made a mistake in the placing of his semi-parenthesis, that he meant to place it after the words 'in earth'. This would most conveniently excise the comma and make Stephens testify in favour of its exclusion. So they would say that wouldn't they? This seems to be standard practice with modern critics. Those who disagree with them, whether ancient or modern, are either deceivers or bunglers. More on this when we consider the subject of Scholasticism below.

Because Stephens' annotations and marginalia state that seven of his MSS omitted the three Greek words only, it follows that the whole verse was present in the rest of them, as he included it in his finished edition.

In further confirmation of this Travis writes,

The Divines of the University of Louvaine, who were contemporaries with R. Stephens, positively affirm, in their Bible, published AD 1574, that ALL the MSS of R. Stephens did contain, not only the epistle of St. John, but this disputed passage also. And this testimony at least, proves the general belief, and reputation, of that age, and time, to be so; and, added to the evidence of Stephen's own marginal references, on this verse, form a body of proof, which no cavils, or conjectures, of modern times.-- which nothing but the production of R. Stephens MSS themselves,--can ever discredit or destroy."14

Regarding the production of the MSS of Stephens themselves, a priest of the Oratory at Paris, Fr. Le Long, claimed in 1720, that all the MSS which Stephens had used, he had found in the Royal Library at Paris. Travis demonstrates that Le Long was mistaken.15

After Stephens, came the editions of Theodore Beza. Travis again,

Theodore Beza...was born in Vezelai, in or about AD 1519 and died in AD 1605. He published an edition of the New Testament, with annotations, at Geneva, in AD 1551. He was urged to this work by Robert Stephens, who, on Beza's compliance with his solicitations, permitted to him the free use of all his Greek MSS. In his notes on this passage of St. John, he says 'This verse does not occur in the Syriac version,' &c. 'but is found in the English MS, in the Complutensian edition, and in some ancient MSS of Stephens...' And he further uses these remarkable expressions ( which indeed, Sir, seems to have drawn down the plenitude of your anger upon him)16 - 'I am entirely satisfied that we ought to retain this verse.'"17

So here we have Travis' account of the principal editions, excluding Erasmus, of what later came to be called the Textus Receptus. We have, given by Travis, 16th century statements that the editors had access to ancient Greek MSS which satisfied them of the authenticity of the comma as Holy Scripture. Then along come Johnny-cum-lately critics, such as Griesbach, two hundred years later, and Metzger et al, four hundred years later, to contradict them.

But Travis also gives details of quotations of the verse by many individuals whom he names from Erasmus up to the beginning of the second century.

He names them, dates them, and quotes them along with references from which all of their quotations were taken.

From the latest upward they are,

Laurentius Valla - 15th C.

Nicholas de Lyra - 14th C.

Saint Thomas - 13th C.

Durandus - 13th C.

Lombard - 12th C.

Rupert of Duyts - 12th C.

Saint Bernard - 11th C.

Radulphus Ardens, Hugo Victorinus, Scotus - 11th C.

"It would be tedious to particularise all the citations made, in this century, of this passage of St. John."18

Walafrid Strabo - 9th C.

Ambrose Ansbert - 8th C.

Elipandus - 8th C.

Cassiodorus - 6th C.

Fulgentius - 6th C.

Vigilius - 6th C.

Eucherius - 5th C.

Jerome - 4/5th C.

Augustine - 4/5th C.

Marcus Celedensis - 4/5th C.

Phaebadius - 4th C.

Cyprian - 3rd C.

Tertullian - 2nd C.

I do not claim that all of Travis' list must be accurate. The best and most upright of men make mistakes. Many of the above names, Metzger, for example, dismisses, as did others before him. We must allow that perhaps in some instances Metzger may be right, but the somewhat wholesale dismissal of many of the above names seems incredible. Travis, as noted above, gives all of his sources and responds to the kinds of criticisms that Metzger raises, from those who went before him. The devil only ever goes away for a season. Once a false teaching is overthrown by godly men in one generation, the devil brings it back when they have died.

Isaac had to re-dig the wells that his father, Abraham, had dug, because the Philistines had filled them in.

A stronger testimony still, however, in favour of the verse, is its inclusion in ancient Council documents or Decretals and Confessions of Faith.

In A.D. 1215, Pope Innocent 3rd convened the Fourth Lateran Council, among other things, I believe, to challenge the teachings of Arianism. At this Council were at least 400 bishops and 800 abbots. Travis writes,

"Among others, the Greek patriarchs of Constantinople, and Jerusalem, were present: and the several patriarchs of Antioch and Alexandria, sent each, a bishop, and a deacon, as their representatives."19

This Council condemned Arianism and included the comma in its act, or decretal.

At the close of the eighth century, we learn from Travis, the Emperor Charlemagne called for a Bible revision. The resulting work was called the Correctorium and contained the comma.

In A.D. 484, King Huneric, the Vandal, and an Arian, convened the Council of Carthage. His professed aim was a debate of Trinitarian and Anti-trinitarians. Around 400 Trinitarian bishops from Africa and the Mediterranean attended this Council only to discover that Huneric's real purpose was to persecute them. Travis says,

"Eugenius [a Trinitarian bishop], and his prelates, withdrew from the council-room; but not without leaving behind them a protest, in which...this verse of St. John is ...insisted upon, in vindication of the belief to which they adhered."20

After these three last examples, Travis continues,

"To the authority of these councils, and to the revision of Charlemagne, let me now subjoin the most sacred sanction, which any collective body of Christians can give to the truth of a passage of Scripture, namely, the admission of it into the public rituals, or service-books, of their churches..."21

The comma was included in the service-books of the Latin Church, the Confession of Faith of the Greek Church, and in the liturgy, or public service-books of the Greek Church.

And, of course, later into the printed texts of Complutus, Erasmus (3rd, 4th and 5th editions), Stephens, Beza and most important of all, for modern man, the King James Bible of 1611.

A final and very important question to be asked under the heading of External Evidence is how do we account for the current small number of MSS which contain the verse? If it is indeed Holy Scripture, why does the MSS testimony not preponderate?

There are a number of factors for consideration and the likelihood is that each played a part to a greater or lesser degree.

First, it may have happened through the drowsiness of an early scribe. His eye, due to the similarity of the verse with verse eight, simply jumped the verse 7 as indeed, modern bibles do on purpose. One such error unnoticed in an early copy might be transmitted into many others.

Secondly, there was much persecution of Trinitarians by Anti-trinitarians, such as referred to above at the Council of Carthage. If violence was resorted to in order to oppose Trinitarian truth, how happily would Anti-trinitarians multiply such copies as omitted the verse. Anti-trinitarianism was very strong during the 4th and 5th centuries.

Thirdly, how sure are we that all extant MSS have been examined at this point? The major repository of MSS documentation is the Institute for New Testament Textual Research in Munster, Germany. Its former head, Kurt Aland, was no friend of the Received Text. He was among the five editors of the United Bible Societies Greek New Testament along with Bruce Metzger and Cardinal Martini, a roman catholic. The UBS text was used as a basis for the NIV. The UBS Greek text says that 1 John 5:7 is certainly spurious. May I be excused for an uneasy feeling about Kurt Aland's textual predilections when he had such control of published MSS data. More data on the modus operandi of the Munster Institute can be found in the work of Dr. Jack Moorman, in particular, When the KJV Departs from the Majority Text.22

For anyone with a taste for it, Travis in the next three letters of his book, responds to Griesbach, Isaac Newton and two other critics of the text at length.

Scholasticism.

"For you see your calling, brethren, how that not many wise men after the flesh, not many mighty, not many noble are called:

But God hath chosen the foolish things of the world to confound the wise: and God hath chosen the weak things of the world to confound the things which are mighty;

And base things of the world and things which are despised, hath God chosen, yea, and things which are not, to bring to nought things that are:

That no flesh should glory in his presence." 1 Corinthians 1:26-29.

"At that time Jesus answered and said ,I thank thee, O Father, Lord of heaven and earth, because thou hast hid these things from the wise and prudent, and hast revealed them unto babes." Matthew 11:25.

Reading through a number of books on this subject, it is quite surprising how often the critics insult both the integrity and the intelligence of those in favour of the verse. Here are just a few examples.

Edward Gibbon, to whom George Travis is writing, refers to the inclusion of the verse in the Complutensian Polyglot as "honest bigotry". The placement by Stephens of the obelus and semi-parenthesis around the words 'in heaven' as "the typographical fraud or error of Robert Stephens". The inclusion of the comma by Theodore Beza, Gibbon refers to as, "the deliberate falsehood or strange misapprehension of Theodore Beza".

In another work by David Harrowar23 in defence of the comma, Harrowar replies to one of his critics and an opponent of the comma. In a message preached after Harrowar's defence of the text, his opponent, one John Sherman, said, "There is not a learned man, at this day, in Europe...who would degrade his character...on the defence of it." That is, 1 John 5:7. Note the implication. If you defend it, you are an ignorant booby. Harrowar responds to this snooty gentleman, saying, "To attack an opponent in the way that the gentleman in opposition has Mr. Travis, betrays the weakness of his cause." Or, as John Burgon put it, "they compensate for the weakness of their arguments by the strength of their assertions."

Be assured, from whichever University you graduated, or however many degrees you may have, if you defend this verse, you will not be accepted as a scholar. Just because all the self-professed eggheads agree does not make it so. Consensus is not science.

Brethren, the dice are loaded!

It is very important to be mindful, that learning without integrity is dangerous. Tozer once said, "The Devil is a better theologian than any of us and is a devil still." Learning is good, but honesty is critical. I find it remarkable that men criticising the texts, writing hundreds of years after, say Jerome, or even Stephens and Beza, will flatly accuse them of ignorance or deceit, when they have no idea to what material they had access all those hundreds of years ago. The current MSS testimony overthrows, with them, any claims that there were in earlier times, more MSS, as testified by the men who used them. I have not seen a Dodo in my lifetime, but I do not claim that there never were any. One suspects that an evolutionary mind-set, encouraging modern scholars to imagine themselves superior, is at work here. Darwin has come to church.

To conclude.

1 John 5:7 is in the Bible! Take this away and you will forever be at the mercy of so-called scholarship. You can never be sure what is scripture and what is not. Is that what God wants?

Footnotes:

1 I have modernised Travis's references to the 'Docetae' . CT.

2 I give the scripture quotations here exactly as I find them in Travis's work, except for removing some capitalisation where it does not conform to the current printing of the KJV. It was common, it seems for English writers from at least the seventeenth century until late in the eighteenth, as here, to use many more capital letters.

3 George Travis, Letters to Edward Gibbon, Esq.,(London, C. F. & J. Rivington, 1785), pp. 331-337. Available from kjvbooks.com.

4 Jack Moorman, WHEN THE KJV DEPARTS FROM THE MAJORITY TEXT OF HODGE AND FARSTAD, CITED BY THE CORRUPT NKJV, (Florida,Faith Baptist Church Publications, 1988), p.116. All of Dr. Moorman's writings are highly recommended and many can be obtained from Kjvbooks.com.

5 T. F. Middleton, The Doctrine of the Greek Article, Applied to the Criticism and Illustration of the New Testament, (Cambridge, J & J. J. Deighton, 1833), p. 441.

6 ibid. p. 441.

7 My apologies to all you Greek scholars out there for omitting the breathings here. I could not find them in my computer software, but you're smart enough to put them in.

8 Middleton, op. cit., p. 441.

9 ibid. p. 453.

10 Travis, op. cit. p. 4.

11 Daryl R. Coates, That Rascal Erasmus, (New Jersey,The Bible for Today, 1994), p. 5.

12 Michael Maynard, A History of the Debate Over 1 John 5:7-8, (Tempe, Comma Publications, 1995), p. 244.

13 Travis, op. cit. pp. 4-6.

14 ibid. pp. 296,297.

15 ibid. pp. 127-138.

16 Referring to Edward Gibbon.

17 Travis, op. cit. pp. 6-8.

18 ibid. p.21.

19 ibid. p.41.

20 ibid, p.45.

21 ibid, p.47.

22 See pp. 4-5.

23 David Harrowar, A Defence of the Trinitarian System in Twenty-Four Sermons, (Utica,1822). Available from kjvbooks.com.