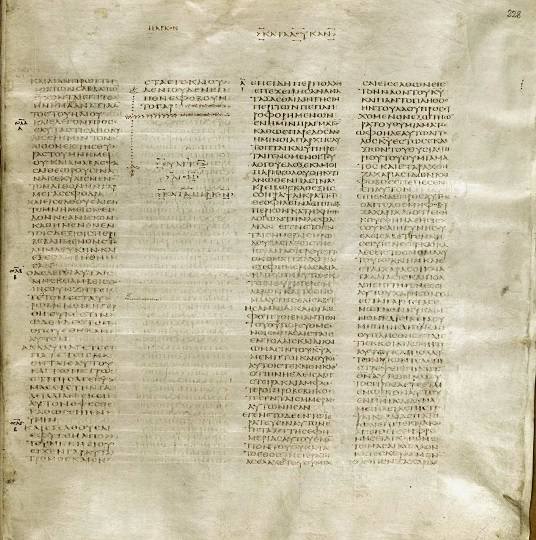

Codex Sinaiticus was found in a trash-can!

A debate took place between Dr. Jack Moorman and Dr. James White a year or two ago which can be viewed on Youtube.

During that debate James White made the following statements.

“I did want to correct just one misapprehension. Sinaiticus was not found in or near a trashcan. That is a common myth, but it’s untrue. All you have to do is read Constantine von Tischendorf’s own first-hand account of his discovery of the manuscript. A monk brought it out of the closet, the cell, wrapped in red cloth. Folks, people in monasteries do not wrap garbage in red cloths, O.K?”

Having read Tischendorf’s account of his discovery of what we now call the Sinaiticus manuscripts some time previously, Dr. White’s assertion rang alarm bells. So let’s turn to Tischendorf;s account and check out Dr. White on this point.

The volume I am referring to is;

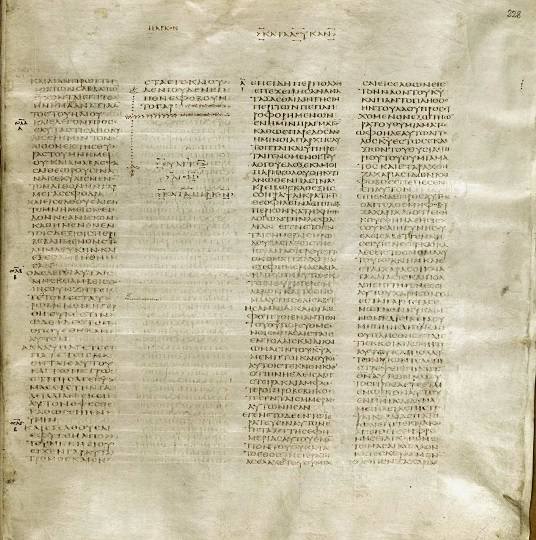

Codex Sinaiticus, The Ancient Biblical Manuscript Now in the British Museum.

Tischendorf’s Story and Argument Related by Himself.

Second Impression of the Third Edition. 1934

London, The Lutterworth Press, 6 Bouverie Street E.C.

Tischendorf’s original account was in German, but my reference copy is an English translation. Bold type in Green are my emphases. In the preface to this eighth edition at page 7 we read,

“The story of the discoveries of the celebrated scholar in 1844 and 1859 is here related in his own words.”

The first thing therefore we must observe is that Tischendorf made at least two visits to St. Catherine’s monastery at the foot of Mt. Sinai. This is subsequently born out in the account following by Tischendorf himself. Furthermore, the translator adds a few facts which are pertinent here. On page 9, the translator refers to,

“…the discovery of the Sinaitic Manuscript, the full particulars of which are given to the English reader in the following pages.”

And on page 10, the translator says,

“We have only to add that this version into English was undertaken with the express approbation of the Author…”

On the strength of these assertions, I believe I hold a reputable account in this volume of the events exactly as they happened.

Now we turn to the words of Tischendorf himself. He writes at page 16,

“In sitting down to write a popular version of my pamphlet, the Zwickau Society also expressed a wish that I should preface it with a short account of my researches, and especially of my discovery of the Sinaitic Codex, which naturally takes an important place in my list of documentary proofs.”

Moving on to page 23, Tischendorf there gives specific details of his first visit to Mt Sinai.

“It was in April, 1844, that I embarked at Leghorn for Egypt. The desire which I felt to discover some precious remains of any manuscripts, more especially Biblical, of a date which would carry us back to the early times of Christianity, was realized beyond my expectations. It was at the foot of Mount Sinai, in the Convent of Saint Catherine, that I discovered the pearl of all my researches. In visiting the library of the monastery in the month of May, 1844, I perceived in the middle of the great hall a large and wide basket full of old parchments; and the librarian, who was a man of information, told me that two heaps of paper like these, mouldered by time, had been already committed to the flames. What was my surprise to find amid this heap of papers a considerable number of sheets of the Old Testament in Greek, which seemed to me to be one of the most ancient I had ever seen. The authorities of the convent allowed me to possess myself of a third of these parchments, or about forty-three sheets, all the more readily as they were destined for the fire. But I could not get them to yield up possession of the remainder. The too lively satisfaction which I had displayed had aroused their suspicions as to the value of this manuscript. I…enjoined on the monks to take religious care of all such remains which might fall in their way.”

“Folks, people in monasteries do not wrap garbage in red cloths, O.K?” says Dr. White.

That’s right Dr. White, they burn it! Unless they perhaps get wind later that someone will pay good money for it.

Tischendorf continues, having returned to Saxony,

“But these home labours upon the manuscripts which I had already gathered did not allow me to forget the distant treasure which I had discovered.[i] I made use of an influential frien, who then resided at the Court of the Viceroy of Egypt, to carry on negotiations for procuring the rest of the manuscripts; but his attempts were, unfortunately, not successful. “The monks of the convent,” he wrote to me to say, “have, since your departure, learned the value of these sheets of parchment and will not part with them at any price.”

We learn on page 24 that Tischendorf made a second visit to the monastery in 1853, “but I was not able to discover any further traces of the treasure of 1844.”

We read of third visit at page 26.

“..in the commencement of January, 1859, I again set sail for the East…By the end of the month of January I had reached the Convent of Mount Sinai…After having devoted a few days in turning over the manuscripts of the convent, not without alighting here and there on some precious parchment or other, I told my Bedouins, on the 4th February, to hold themselves in readiness to set out with their dromedaries for Cairo on the 7th, when an entirely fortuitous circumstance carried me at once to the goal of all my desires. On the afternoon of this day I was taking a walk with the steward of the convent in the neighbourhood, and as we returned, towards sunset, he begged me to take some refreshment with him in his cell. Scarcely had he entered the room, when, resuming our former subject of conversation, he said: “And I, too, have read a Septuagint” – i.e. a copy of the Greek translation made by the Seventy. And so saying, he took down from the corner of the room a bulky kind of volume wrapped up in a red cloth and laid it before me. I unrolled the cover and discovered to my great surprise, not only those very fragments which, fifteen years before, I had taken out of the basket, but also other parts of the Old Testament, the New Testament complete, and, in addition, the Epistle of Barnabas and a part of the Pastor of Hermas. Full of joy, which this time I had the self-command to conceal from the steward and the rest of the community, I asked, as if in a careless way, permission to take the manuscript in to my sleeping chamber to look over it more at leisure. There by myself I could give way to the transport of joy which I felt. I Knew that I held in my hand the most precious biblical treasure in existence – a document whose age and importance exceeded that of all the manuscripts which I had examined during twemty years study of the subject.

And there we have it. When we turn as James White directs us to Tischendorf’s account, we find no such thing as White asserts. No doubt, it was only after the monks perceived Tischendorf’s excitement, that realizing the age of the document, they “would not part with it at any price”, and wrapped it in red cloth.

KJV only advocates are right therefore, when we claim that Sinaiticus was found in a waste paper basket. No mythology here!

[1] Dean John William Burgon, who, unlike Tischendorf, combined faithfulness with his considerable scholarship had this to say about Tischendorf. “Which of this most inconstant critic’s texts are we to select? Surely not the last, in which an exaggerated preference for a single Manuscript which he has had the good fortune to discover has betrayed him into an almost child-like infirmity of critical judgment.” And again, “It has been ascertained that his discovery of Codex Aleph caused his eighth edition (1865-72) to differ from his seventh in no less than 3505 places, -“to the scandal of the science of Comparative Criticism, as well as to his own grave discredit for discernment and consistency.””

Colin Tyler